The Fire

Tuesday • December 23rd 2025 • 7:53:19 pm

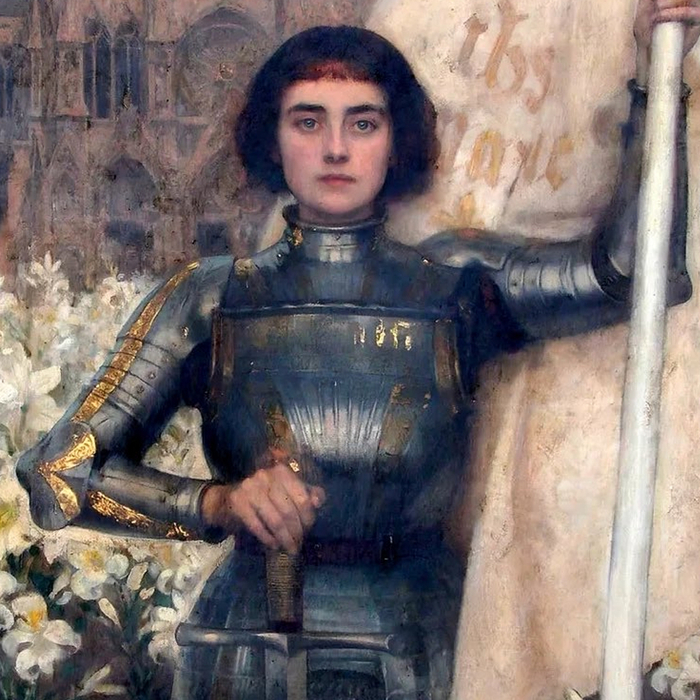

"France, lost by a woman, shall be saved by a virgin from the marches of Lorraine." — The Prophecy of Merlin

PROLOGUE

Rouen, 1431 — Holy Night, Dangerous Night

To this day, people think that medieval times were dumber times—an age of servitude and superstition, where peasants bent their backs and never raised their eyes. They could not be more wrong. And what happened that night serves as perfect proof. The men who moved through Rouen's darkened streets were not peasants. They were engineers, strategists, diplomats, and soldiers who had studied mathematics in Paris, medicine in Montpellier, and warfare on a hundred battlefields. They spoke Latin, Greek, and three dialects of French. They understood leverage—both mechanical and political. They had planned this operation for eleven months, and they had planned it with the precision of a cathedral's construction. The atmosphere was so severe that nothing could go wrong. These men were not merely focused—they were carrying out an epic historical duty, like few others in the long chronicle of France. They moved like shadows given purpose, like prayers given flesh.

Had anything gone wrong, the woman under their protection would remain unharmed. But there would be consequences. Terrible consequences. Every man among them had sworn the same oath: if they failed tonight, there would be no church left standing between Rouen and Rome. They had the means. They had the fury. And they had been pushed to the very edge of what men of honor could endure.

The city was surrounded—not by an army, for armies could be seen, but by something far more dangerous: a network of loyal Frenchmen who had infiltrated every guild, every tavern, every guardhouse. The English thought they held Rouen. In truth, Rouen held its breath, waiting.

The only unusual sign the extraction team could see was that everyone seemed awake. Behind shuttered windows, candles burned. Old women clutched rosaries. Children had been told to stay silent—not by their parents, but by something older, some inherited memory of what France owed to its protectors.

Silence. Magnitude. Precision. These defined the night.

PART ONE

THE WOUND IN FRANCE'S HEART

To understand Joan—to truly understand what she became and why she had to become it—you must first understand what France had done to itself.

The year was 1407 when the Duke of Orléans was murdered in the streets of Paris by assassins sent by his own cousin, John the Fearless of Burgundy. With that single act of fratricide, France tore itself in two. The Armagnacs rallied behind the murdered duke's son. The Burgundians followed John. And for a generation, Frenchmen slaughtered Frenchmen with a fury they had never shown the English.

This was not politics. This was not strategy. This was something far older and far uglier—a blood feud that consumed entire families, entire towns, entire provinces. A farmer in Picardy might wake to find his neighbor's house burning, not because of any personal quarrel, but because one family wore the white cross of Burgundy and the other the red band of Armagnac.

Children grew up not knowing if their uncles were alive or dead. Mothers taught their daughters to hide when men rode into the village—not English raiders, but Frenchmen, their own countrymen, wearing colors that meant death. A merchant who traded in Burgundian territory might be hanged if he crossed into Armagnac lands. A priest who gave last rites to an Armagnac soldier might find his church burned by Burgundian knights.

And into this open wound stepped the English. They did not conquer France—France had already conquered itself. Henry V merely walked through the door that French hatred had opened. At Agincourt, French knights cut each other down in their rush to reach the English lines, their rivalry so fierce that they could not even cooperate against a common enemy. By 1420, the madness had reached its zenith. The Treaty of Troyes—signed by the very King of France—disinherited the Dauphin Charles and gave the crown to the English King Henry. A French queen had sold her son's birthright. A French king had signed away a thousand years of sovereignty. And Burgundy stood smiling, believing it had won.

This was the France into which Jeanne d'Arc was born. A France of divided loyalties and broken families. A France where the question 'What are you?' was answered not with 'French' but with 'Armagnac' or 'Burgundian.' A France where hope had become a thing remembered only by the old.

In the village of Domrémy, on the border between worlds, a girl grew up hearing stories. Not the stories of saints that the priests told—though she heard those too—but older stories. Stories of Merlin. Stories of prophecy. Stories of a virgin who would come from the marches of Lorraine to save what men had destroyed.

Most children heard such tales and forgot them. Jeanne heard them and remembered. More than remembered—she studied them. She asked the old women what exactly the prophecy said. She pressed the traveling merchants for versions they had heard in other towns. She collected every fragment, every variation, and she saw in them not a distant legend but a blueprint.

At twelve, she began her preparation. Not in the fields, but in the margins of her life—in the extra hours before dawn, in the stolen moments during festivals when others danced and she observed. She studied the men who came to recruit soldiers. She noted how they spoke, how they stood, how they commanded. She watched the priests and learned their rhetoric. She listened to the merchants and understood how information traveled.

Jeanne d'Arc did not stumble into destiny. She built it, stone by stone, with the patience of a cathedral architect and the precision of a master strategist. She saw the prophecy not as fate but as instruction. Not as something that would happen, but as something she could become.

She was not a little nineteen-year-old girl swept up by forces beyond her understanding. She became exactly what the prophecy foretold—because she had made it her life's work to do so.

PART TWO

THE EXTRACTION

The cell door opened without a sound. They had spent four months bribing the right blacksmith to forge the right hinges. Jean de Metz was the first through. He had been with her since Vaucouleurs, since the very beginning, when a teenage girl had walked into a garrison and demanded an army. He had believed her then. He had never stopped believing. Behind him came Jean d'Aulon, her loyal steward, who had fought beside her at Orléans and Patay and a dozen nameless skirmishes where the fate of France hung by threads of steel and courage.

She was sitting in the corner, hands folded, as if she had been expecting them. She had simply calculated the odds and known that they would come. They had to come. Not merely because they loved her, though they did, with a devotion that surprised even themselves. But because France could not survive without her.

"You took your time," she said. No fear. No relief. Just that quiet humor that had carried her through a year of captivity. "We had to make certain arrangements," d'Aulon replied. "You'll appreciate them later."

They moved through passages that should not have existed—tunnels that had been dug by masons who asked no questions because they knew, in their bones, what they were building. They emerged into a courtyard where horses waited, held by men whose faces were hidden but whose loyalty was absolute.

The Dauphin—now Charles VII, though he had never been crowned, not properly, not yet—had wanted to send an army. Isabelle de Lorraine, the gentle duchess who had become Joan's closest confidante, had convinced him otherwise. An army would be seen. An army would be stopped. But eleven men and one woman, moving through the night with the blessing of every peasant between Rouen and the Loire? That was something the English could never prevent. You cannot guard against a people who have decided, collectively and in their hearts, to save what they love.

By dawn, they were thirty miles from Rouen. By the second night, they had crossed into territory held by forces loyal to Charles. And by the third morning, Jeanne d'Arc—the Maid of Orléans, the terror of English ambitions, the virgin foretold by Merlin—had vanished from history.

PART THREE

THE QUEEN OF SHADOWS

For thirty years, she had no name. Or rather, she had a hundred names, and none of them were Jeanne. The world believed the Maid of Orléans had burned. The English had made certain of it—or thought they had. They had staged an execution with a condemned woman whose face was hidden by flames and smoke. They had scattered ashes into the Seine. They had declared, with all the pompous certainty of occupiers who mistake terror for legitimacy, that the witch was dead. But networks that had been built to smuggle weapons could also smuggle people. Safe houses that had hidden resistance fighters could hide something far more valuable. And the thousands of ordinary French men and women who had witnessed her miracles at Orléans and Patay—they kept her secret with the ferocity of parents protecting a child. From a farmhouse in the Loire Valley, from a manor in Provence, from a dozen locations that changed with the seasons, she built something that had never existed before: an intelligence network that spanned all of France. Merchants who traveled between cities carried her messages. Priests who heard confessions passed along the sins of English collaborators. Servants in noble houses reported on their masters' plans. And at the center of it all, unseen and unnameable, sat the woman the network called simply La Reine—The Queen.

She never commanded armies again. She had learned—had been taught, through fire and betrayal—that direct power could be captured and corrupted. But information? Influence? The ability to know what your enemies planned before they planned it? That was a weapon that could not be seized on a battlefield or burned in a market square. Charles VII—who had finally been crowned at Reims, just as she had always known he would be—ruled France in name. But it was La Reine who knew which English commanders could be bribed and which should be assassinated. It was La Reine who identified the Burgundian nobles whose loyalty could be turned. It was La Reine who ensured that every English advance was met not by armies, but by something worse: by food shortages that appeared from nowhere, by bridges that collapsed at convenient moments, by secrets that found their way to exactly the right ears.

Her allies knew her. The Dauphin visited her in secret, seeking counsel on matters that histories would later attribute to his own wisdom. Jean de Metz grew old in her service, becoming the visible hand of an invisible queen. Jean d'Aulon trained the next generation of her agents, teaching them that loyalty to France meant loyalty to her, whether the world knew her name or not.

And Isabelle de Lorraine, her dearest friend, the woman who had argued most fiercely for the extraction, brought her news from the courts of Europe. Together, they watched the English grip on France weaken, year by year, until what had seemed impossible in 1431 became inevitable by 1453: the final expulsion of the English from all French soil except Calais. The history books would credit generals and kings. But those who knew—those who truly knew—understood that France had been saved by a ghost. By a woman who had chosen to die so that she could truly live. By the fire foretold, burning not in a market square, but in the hearts of everyone who had ever believed in something greater than themselves.

PART FOUR

THE RECKONING

She had made them a promise, in those first days of freedom. Not a promise of mercy—she had spent eleven months learning what mercy meant to men who sold their souls for English gold. But a promise of justice. A promise that every man who had conspired to destroy her would face the consequences of his choice.

Not bloody revenge. That would make her like them. But justice—true justice—meant that each man would be undone by the very corruption that had led him to condemn an innocent woman. Each would face his end by the weight of his own sins.

Pierre Cauchon, Bishop of Beauvais, had sold his integrity for a promise: the English would make him Archbishop of Rouen. He had crafted the trial, twisted the theology, forced the condemnation. He had watched the flames—or what he thought were flames—with satisfaction, believing his reward secure.

The reward never came. The English, who used corrupt men without respecting them, found reasons for delay. Year after year, Cauchon waited. Year after year, his letters to London went unanswered. And as he waited, things began to go wrong. Witnesses from the trial began to recant. Whispers spread that the execution had been a sham. Rumors reached Rome that the Bishop of Beauvais had condemned a saint.

She visited him once, three years before his death. He did not recognize her—how could he? The woman he had condemned was supposed to be ash and memory. But she sat across from him in his study, an unremarkable visitor seeking spiritual counsel, and she listened as he spoke of his disappointments, his frustrations, his growing certainty that God had abandoned him.

"Do you ever think of her?" she asked. "The Maid?"

"Every day," he admitted. "Every day I wonder if I made a mistake. Every day I wait for the punishment that seems certain to come."

"Then you have already begun to pay," she said. And she left him to his nightmares.

Cauchon died in 1442, alone in his chambers. The physicians called it apoplexy. His servants whispered of poison—a slow poison, they said, that had been working through his system for years. They found him clutching a letter that had finally arrived from the Pope, requesting his presence in Rome to answer questions about the trial of Jeanne d'Arc. He had died before he could face judgment. Or perhaps that was his judgment—to die in anticipation of an accounting he would never get to make.

Jean Lemaître, the Vice-Inquisitor who had lent the authority of the Church to Cauchon's farce, was a weaker man. He had known the trial was wrong. He had said so, privately, to anyone who would listen. But he had signed the condemnation anyway, because refusing would have cost him his position.

In the years that followed, his weakness became his prison. Every knock at the door might be a messenger from Rome. Every stranger might be an agent of the King, come to arrest him for complicity. He began to see the Maid everywhere—in the face of a serving girl, in the posture of a woman at prayer, in the flames of his own hearth.

She never visited him. She didn't need to. His own guilt was the most effective torturer. By 1450, he had retreated entirely from public life, refusing to leave his chambers, convinced that the woman he had helped condemn was waiting for him in every shadow.

When they found him, he was raving about voices—voices that told him his soul was forfeit, voices that promised an accounting he could never escape. The Church called it madness. Those who knew the truth called it something else: the sound of a guilty conscience finally breaking.

The Maid of Orléans was undefeated. She had not even needed to raise her hand.

Geoffroy de la Mothe had been one of the assessors at the trial—a minor figure who had voted for condemnation in hopes of English favor. He received that favor, for a time: a comfortable living, a position in the English administration, the wealth that came from serving the occupiers.

But La Reine's network was patient. They found his ledgers, his records of properties seized from French families who had resisted the occupation. They found evidence of bribes, of embezzlement, of a dozen petty corruptions that the English had overlooked because he was useful. And they ensured that this evidence found its way to precisely the people who would act on it.

The English arrested him for financial crimes. His properties were seized. His family was disgraced. By the time France reclaimed the territory where he had built his fortune, Geoffroy de la Mothe was living in a single room in Calais, begging for scraps from the same English masters who had once rewarded his treachery. He died in poverty, unmourned, having lost everything he had sold his honor to gain.

Guillaume Érard had preached the sermon at Joan's condemnation—a vicious piece of rhetoric that called her a heretic, a schismatic, a limb of Satan. He had done Rome's bidding, for Rome had political reasons to support the English against France, and Érard was nothing if not a creature of political convenience.

But political convenience cuts both ways. As the war turned against England, as French victories mounted and English control crumbled, men like Érard became liabilities. He knew too much. He had been too visible. And the underground—that network of patriots who answered to La Reine—made certain that his masters understood exactly how much of a liability he was.

He was found in an alley in 1443, killed by unknown assailants. The English authorities investigated half-heartedly, concluded that it was robbery, and closed the matter. But no valuables had been taken. And on his body was found a white lily, pressed and dried, which no one could explain and no one chose to investigate further.

Jean d'Estivet had been the prosecutor—the man who had crafted the charges, who had twisted her words, who had worked tirelessly to ensure her condemnation. He had been efficient, thorough, utterly without conscience. The perfect instrument of judicial murder.

His death was not subtle. It was not quiet. It was exactly the kind of end that a man who had shown no mercy might expect from those who remembered his crimes.

They found him in a drainage ditch outside Rouen, in the same city where he had prosecuted the Maid. The official cause of death was exposure—he had been drunk, they said, and had fallen into the ditch and could not climb out. But witnesses had seen him being escorted from a tavern by men he seemed to know. And the nature of his final hours—cold, alone, crying for help that never came—seemed to those who remembered Joan's trial to be a fitting reflection of what he had done to her.

Henry Beaufort, Cardinal and Bishop of Winchester, had been the architect of the English effort to destroy Joan. He had not soiled his hands with the trial itself—he was too important for that—but he had funded it, directed it, and ensured that English political interests were served by her condemnation. He had looked into her eyes at Rouen and seen not a person but an obstacle to English ambitions.

Joan never visited him. She never sent agents against him directly. His downfall came from something simpler and more devastating: his own legacy.

As the English position in France collapsed, Beaufort watched everything he had worked for crumble to dust. The territories he had schemed to control fell back into French hands. The Church hierarchy he had cultivated turned against England. The money he had spent on endless warfare had achieved nothing—less than nothing, for it had exhausted English resources and English will.

He died in 1447, reportedly crying out about the futility of his life's work. "What use is wealth?" he is said to have asked on his deathbed. "What use is power? I have spent my life building, and everything I built is gone." The Cardinal who had condemned a saint died knowing that history would judge him, and judge him harshly. That was punishment enough.

Catherine de la Rochelle had claimed to have visions too—visions that told her Joan was deceived, that the Maid's voices came not from saints but from demons. She had denounced Joan to the English, hoping to replace her as France's visionary, hoping to claim the authority that Joan had earned.

She had been a fool rather than a villain, and La Reine recognized the difference. Catherine had been manipulated by forces she did not understand, used by Rome as a counterweight to Joan's influence. There was sin in what she had done, but also ignorance. And ignorance could be forgiven.

Joan's agents found Catherine in 1435, living in poverty and disgrace. Her false visions had earned her nothing. The English had discarded her the moment she was no longer useful. She was bitter, broken, convinced that God had abandoned her. They offered her a choice: continue as she was, forgotten and despised, or serve France as she should have served it from the beginning. Catherine chose service. For twenty years, she worked as a double agent, feeding false information to the network of Roman spies who had originally deployed her. She never knew who she truly served—La Reine kept her identity hidden—but she understood that she was working to undo the harm she had caused.

It was not forgiveness. But it was redemption, of a sort.

Nicasius of Rouen had been another assessor, another minor figure who had voted for condemnation because that was what his superiors expected. Unlike some of the others, he had felt genuine remorse—not enough to refuse the English, not enough to speak the truth, but enough to haunt him in the years that followed.

La Reine visited him personally, more than once. These were not threatening visits. They were conversations—quiet, careful conversations about theology and conscience, about the nature of guilt and the possibility of atonement. "Do you believe," she asked him once, "that a man who commits a sin unknowingly is as guilty as one who sins with full knowledge?"

"No," he said. "But I knew. I knew she was innocent, and I condemned her anyway." "Then you understand your sin. That is the beginning of repentance."

His fall from favor came not through her agents but through his own conscience. He began to speak publicly about the trial's irregularities. He testified at the rehabilitation proceedings that eventually cleared Joan's name. He spent his final years in poverty, having given away his wealth to the families of those who had suffered under English occupation. Joan could have destroyed him. Instead, she gave him the chance to destroy his sin. It was, perhaps, the closest thing to mercy she allowed herself to show.

EPILOGUE

The Fire That Never Died

She lived to see France whole again.

She lived to see the English driven from every fortress, every city, every village they had stolen. She lived to see Burgundy reconciled with the crown. She lived to see the treaty that ended the war—not in English triumph, as her enemies had promised, but in English defeat, complete and irreversible.

She lived to see her name cleared. In 1456, twenty-five years after her supposed execution, the Church conducted a formal rehabilitation trial. Witnesses who had been silent for decades finally spoke. Evidence that had been suppressed finally emerged. And Joan of Arc—the Maid of Orléans, the virgin foretold by Merlin—was officially declared innocent of all charges. She did not attend the proceedings, of course. The woman who had orchestrated them could not reveal herself without undoing everything she had built. But she read the transcripts, delivered to her by messengers who did not know their recipient. And she allowed herself, for the first time in twenty-five years, to weep.

Not tears of grief. Not tears of relief. Tears of completion. The girl who had read of Merlin's prophecy in a village on the border of nothing had become the woman the prophecy described. She had saved France, not once but twice—first with sword and banner, then with shadow and silence. She had fulfilled her destiny not by surrendering to it, but by choosing it, day after day, for forty years.

History would remember her as a martyr. That was fitting. Martyrs inspire. Martyrs unite. Martyrs burn forever in the hearts of those who believe in something greater than themselves.

But the truth? The truth was known only to a few: to the aging King Charles, who visited her grave and wept for the woman who had given him his crown. To the children of Jean de Metz and Jean d'Aulon, who had grown up hearing stories of a queen without a kingdom. To the peasants of a hundred villages who had protected her secret, generation after generation, because France remembers those who fight for her.

The fire foretold by Merlin was not the fire that the English had lit in Rouen's marketplace. That fire had been a lie, a symbol, a puppet show staged by men who mistook destruction for power.

The true fire was something else entirely. It was the fire that burned in the hearts of every French man and woman who refused to surrender. It was the fire that illuminated the darkest moments of the occupation and guided the resistance through years of seeming hopelessness. It was the fire that Jeanne d'Arc had kindled with her courage and fed with her sacrifice.

That fire never went out. It burns still.

She died in 1477, at the age of sixty-five, surrounded by those who loved her. Her grave is unmarked—she requested it that way. Let history remember the Maid, she said. Let the woman rest.

But sometimes, in the small villages of the Loire Valley, in the country churches where old women still light candles to the saint who saved France, you can hear a different story. A story of a queen who never sat on a throne. A story of a fire that the English could not extinguish. A story of justice—patient, implacable, absolute—visited upon every man who tried to destroy the light of France.

They say that if you listen closely, in the quiet hours before dawn, you can still hear her voice. Speaking, softly, to those who have the courage to listen: "France, lost by a woman, shall be saved by a virgin.

And she shall not fail.

She shall never fail.

Not as long as there is one heart that remembers.

Not as long as there is one soul that believes.

Not as long as the fire still burns."

FIN

~

To Joan. Merry Christmas, old frend.